![]()

|

Turks had the tradition to illustrate manuscripts during the cultural periods before Islamic belief. Paper that could be rolled started to be made in China with plant fibers in 105 B.C. No written or illustrated document has yet been found from the time of the Chinese Han dynasty, of Huns and G÷kt’rks.Nevertheless, the large quantities of stone engravings, textiles,ceramics, works of art made of metal, wood, leather which have survived to the present day, prove that the above mentioned cultural circles were quite developed in other fields of art. The oldest examples of Turkish pictures for walls are from the 6th, 7th and 8th centuries. The withering influence of natural conditions have prevented the survival of these first examples. |

The Oldest Turkish Illustrated Documents |

| The

oldest illustrated documents on paper among Turkish tribes, are from the period succeeding

Akhuns. These documents dating from 717-719 are in Turkish, Chinese and Arabic and

they belong to a Turkish emir who battled with Moslem armies in Pencikent near Samarkand.

This prince was taken prisoner, and his palace was ruined 722. The wall drawing are the

most important part of Turkish cultural treasures. Von le Coq who has researched

Central Asian Turkish culture writes this: "Turks have scattered all of their written

cultural products in the dusty roads of steppes and deserts while migrating to the

west." Prophet Mohammed tranquilizes the dragon on the way of the caravan, "Siyer-I Nebi" end of the 16th century. Samarkand was renowned during 6th-8th centuries by its drawing workshops where illustrations on wood, plaster and leather were made. These works influenced greatly the Anatolian Seljuk period. The most important development of the 9th century Uygur Turks in the art of painting, was accomplished by the painters and their school in the town of Kizilkent. Their sense of light in pictures and their search for the influence and impression of shadow and light, served largely for the formation of Seljuk miniature school and canalized it. The Tun-Huang monastery and library of Uygur Turks has a special importance. Among thousands of books in the library there are the oldest Turkish gilded and miniature manuscripts. The oldest wooden print and illustrated book in the world belongs to Uygurs and is in the above library. The date of the book is 868. Another important aspect of this find is that some manuscripts have been written in letters same with the ones on the G÷kt’rk Orhun epitaphs. |

Moslem Miniatures |

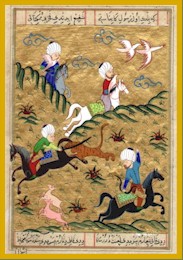

| The oldest miniatures found in Moslem circles are from the 9th, 10th, 11th centuries and they have been found in Egypt. Islamic sources of later periods also confirm this fact. Seljuk Turks established the first school of miniatures in Baghdad within their vast empire covering Turkestan, Iran, Mesopotamia and Anatolia in the 12th century. This school has continued until the end of the 14th century, but the most important works and examples are from the 13th century. "The Seven Sleepers", Important characters in history 1583 Islamic culture was influenced also by antique heritage in the field of miniatures. The books of the antique age were read and translated. These manuscripts were illustrated. Moslems used these original illustrations in the translations; but although the text were not changed in the later translations, the miniatures were made differently. There are even differences of style in these early works. The miniatures of the antique age are disorganised and most of them have descriptive qualities. In Seljuk miniatures, on the contrary, the subject was composedly depicted. The subjects were taken from the antique age, whereas the style was influenced by oriental, Uygur painting. The main characteristics of the Seljuk-Baghdad school were vigour, briskness, power of expression, caricature quality, over ornamentation, lack of scenery and accentuation of figures. Before starting to study the Ottoman miniature, I shall refer to two more schools of miniature related to Turks. This attitude has a main reason, and that is the inevitable necessity to know the contradictory schools in order to comprehend to one under study. The Chinese influence in the 14th century Mongolian miniatures, is felt in the landscapes made with Chinese ink. The dominant characteristics of those pictures were Chinese style clouds, the curved lines and flower outlines. The colours were dull. There were no figures in the early works. Scenery and figures have been united in the Mongolian miniatures after the Chinese influence ended. Realism, portrait Characteristics, light and shadow, perspective were dominant in large figures. The figures got smaller towards the end of the 15th century, during Tamerlane reign. The surfaces were covered with superficial and decorative all over designs. The dominant subjects were romantic stories. The animals in "Kelile and Dimne" fables were pictured within sceneries. Folk stories such as "H’srev and Shirin", "Leyla and Mecnun" have been depicted in the poetic atmosphere of poet Sadi. The abstract expression gave the same value to each figure as in the carpet motifs. |

The 16th Century Ottoman Miniatures |

| The

conquest of Istanbul was the first step into a new phase of the Ottoman cultural life. The

characteristics of the period in the field of paintings and miniatures may be summed up as

the meeting of the eastern and western painting schools, as the widespread interaction and

communication and as the widespread availability of display. While the H’srev and

Shirin, Sheraz school in the beginning of the 15th century, Iran Italian painters called

by Mehmet the Conqueror continued their activities, Turkish artists on the other hand,

carried on the domestic traditions. We can see this dual influence in the works of Sinan

Bey from Bursa, who was the pupil of H’samzade Sunullah and Master Paoli. Meanwhile,

upon closure of the Heart academy for painting in the beginning of the 16th century, its

famous instructor Behzat was met with a deserved esteem in Tabriz in 1512. His pupils

began to produce works in his style. Their works reached the gates of Istanbul. Sultan

Selim Iran and Aleppo to Istanbul after the seizure of Tabriz and he ordered his men to

create favourable conditions for those artists' work. Soon after Shah Kulu from Tabriz was

leading these artists in an academy which was called by the Turks "Nakkashanei-i

Irani" (The Persian Academy of Painting). "Nakkashane-i Rum" (The Ottoman

Academy of Painting) was established upon the reaction of the Ottoman painters. It goes

without question that the period beginning with Mehmet the Conqueror and ending with

Sultan Selim I, was one of the most interesting and important phases in Turkish painting

and miniatures. Various styles and ways of expression were searched, the influences were

are guide and syntheses were attained. Now we shall take a look at the Turkish Academy

during S’leyman the Magnificent reign. Turkish miniature lived its golden age during

that period, with its own characteristics and authentic qualities. The most renowned

artists of the period were Kinci Mahmut, Kara Memi from Galata, Naksi (his real name

Ahmet) from Ahirkapi, Mustafa Dede (called the Shah of Painters), Ibrahim Ěelebi, Hasan

Kefeli, Matrak‡i Nasuh, Nigari (who portrayed Sultan Selim II and whose real name was

Haydar. He was a sailor). Miniature was again on full force during Murat III's reign. The famous miniature painters of the age were master Osman, Ali Ěelebi, Molla Kasim, Hasan Pasa and L’tf’ Abdullah. We should also mention the Persian, Albanian Bogdanian and Hungarian artists who largely contributed to the art of miniature in the cosmopolitan Ottoman society. According to the registers of the 16th century, the number of miniaturists in S’leyman the Magnificent's court only were 29 instructor-masters and 12 apprentice-pupils. These numbers increased highly towards the end of the century. Few of the miniatures are dated. The miniaturist signed his work only if he alone has painted the portrait or the scene. The works were usually anonymous. The head painter used to draw the main composition with thin brushes and then his assistants and pupils painted in part by part. It is difficult to distinguish individual styles. The head painter, the author and writer of the story were also depicted in some of the miniatures. The most refined lines forming the basis of the picture were the lines bordering spaces, the lines on coloured surfaces and the lines of facial expression. The design approach was usually symmetrical. The terms of the age were: "Nakis-miniature; nakkaspainter, miniaturist; tasvir-depiction; m’savvir-depicter; nakkashane/nigarhane-workshop; kalemi siyah-pencil; sebil yazmak-to portray; tahr-composition; tarrah-designer of the composition; endam-symmetry, balance; nakkasan group of miniaturists. The beauty of the Turkish miniatures spring from the contours and the sense of colour. The paper straightened by a heavy press was covered by red lead. The finish consisted of egg-white, starch, lead carbonate, gum tragacanth, salt of ammonia. The finished paper had a luminous appearance and it was creamy in colour. After the text and tables were completed, the paper was handed to the miniaturists to be painted. The miniatures were divided as 1)Illustration of books, compositions (depiction of certain subjects and events) and 2)portraits. The subjects of the miniatures were as follows: Shahname and Shehinshahname-The public and private lives of rulers, their portraits and historical events; Shemaili Ali Osman-portraits of rulers; Surname-pictures depicting weddings and especially circumcision festivities; religious subjects (Siyer-i Nebi); Shecaatname-wars commanded by pashas; Iskendername-in ancient Moslem belief Alexander the Great is considered a prophet; Humayunname-epics, heroic deeds and animal fables; literary works and folk stories such as Leyla and Mecnun; anthologies; the world of botanies and animals, scientific books on alchemy, cosmography and medicine; technical books; love letters; horoscopes translations.The miniatures in the translations were sometimes directly copied from the original and sometimes they were authentically made. In such cases, ones should know the different styles of the other Moslem miniatures such as Iran and India. Kaaba depictions, sports and especially horse-riding scenes took place in the Turkish miniatures. Portrait of Murat III. "Important Characters in History, 1583" The clear and simple expression attained a magnificent style by plain drawing and colours. There was neither lyricism nor idealism, but only realism based on close observation. There were humorous expressions of daily life. This expressionist style revealed itself in a very few lines in the moving bodies. Refined details were rare. The purpose was to reflect and attain the best within simplicity. The combat order were shown on war miniatures. It is understood that the miniaturists joined those campaigns. The artists did not consider perspective and the third dimension. They portrayed people in straight profiles or from the front instead of the three fourth profile seen in Persian miniatures. The relation between nature, objects and figures was not taken into consideration. The relation between nature, objects and figures was not taken into consideration. The important point was the main theme. The secondary themes and scenes were complementary to the composition. The borrowed look of the figures indicate that they were the ordinary individuals of protocol in every period. Pride, faithfulness and anxiety signified the order of the state with a humorous approach. The composition and the contours were worked attentively. The order of places was very important. Realistic scenery and topographic views were rare. Artists like Matrak‡i Nasuh who depicted the Iraqian campaign of S’leyman the Magnificent with details of the resting places and the Mediterranean ports, were very few. The colours were obtained by powdered dyes mixed with egg-white. The colours were strikingly brilliant. Contrasting colours were used side by side with warm colours with an avant-garde approach in colour selection. In nature depictions spots of colour were used. The colour nuances of the same shade were masterly applied. The most used colours were bright red, scarlet, green and different shades of blue. The domes were painted pale blue. The way black, white, yellow and gild were used liberally had a special quality. Gild was used in architectural details, in the background and the ground of calligraphic works. The sky and clouds were never depicted in their natural colours. Turkish art of miniature, as all the other handcrafts, followed the historical line of the state and had its golden age during the 16th century. Turkish-Islamic Art; The Miniatures of the Zubdat-al-Tawarikh

|